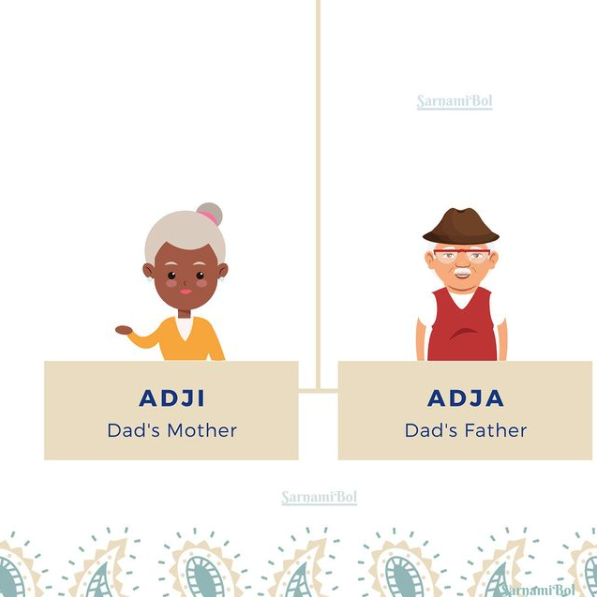

As an Indo-Caribbean person with both Guyanese and Surinamese heritage, it’s been really interesting to contrast and compare the two different (South-)Asian diasporas. Both my Nani (maternal grandmother) and Adji (paternal grandmother) are from Guyana.

My Adji (and her brother) moved in with her aunt in Suriname after the death of her mother. She was only a child then. Years later, she married a Surinamese man, fully integrating in Surinamese culture. It was only after my Adji’s death that I got to know about her (half-) siblings. Indo-Guyanese relatives spread over North America. I learned that my Adji’s ancestral line is also Madrassi, and that her maternal grandparents spoke a version of Tamil. That was really exciting news, because I have very limited information on my heritage, so I love knowing more even if that only means piecing together tidbits here and there.

Even with all the limited information, I’ve noticed that we’re losing our language.

Most of my insights into the Guyanese diaspora comes from my mother’s side of the family. My Nani moved to Suriname at 18 after she married my Nana. She’d spent her formative years in Guyana, and she came from a more tight-knit family than my Adji. When it comes to language, my Nani would speak Guyanese (an English-based creole language) and Guyanese Hindustani (a dialect of Bhojpuri, mixed with other influences) with her family. Half half, as she would put it. Nani had also learned a bit of Hindi through school and through her mother, who also read stories of the Ramayana.

The few times I had met my Guyanese side of the family, which had been in both Suriname and Guyana, they had only spoken in Guyanese. It wasn’t until I was 18 and visited my family in New York, after they had all migrated, and I met my Nani’s sister for the first time that I heard someone from Guyana speaking in Guyanese Hindustani. She looked and sounded exactly like my Nani, whom I hadn’t seen in years.

I really enjoyed spending time with my Nani’s sister, it was almost like spending time with my own Nani. It felt so much like home. The way she talked, the way she looked, and even the food she cooked was similar to what I was used to. At the same time, it stood out to me that my aunts, my mother’s cousins, didn’t speak the language, only English and Guyanese. And the generation after that, my generation, they definitely didn’t speak Hindustani.

If I compare this to the Surinamese counterpart, based solely on my experiences, then Sarnami Hindustani (dialect of Bhojpuri but with different external influences) is still actively spoken by most generations currently living in Suriname. In fact, it’s the third-most spoken language after Dutch and Sranan Tongo. In the Netherlands, however, this is a different story. My generation, usually first generation Surinamese-Hindustani born in the Netherlands, has a great loss of their heritage language or mother’s tongue too.

I wasn’t born in the Netherlands, but I was a young child when I came here. Like my Adji, I lost parts of my heritage too. In my case, my language. I’d gone from speaking Sarnami Hindustani to speaking Dutch in a matter of months. This loss is known as language attrition (my academic background in literature and linguistics is serving a purpose! Yay!).

Now I only passively know my mother’s tongue. My parents have always spoken it to me, so I still understand it, and if I put in some effort I would be able to speak it too (albeit with grammatical errors and a cringeworthy Dutch accent). There’s a part of me that wants to relearn it again, as a way to keep my heritage alive.

Though I’ll be honest, the reason why I haven’t yet is because the culture I grew up in doesn’t really allow for imperfections or mistakes. Not even when it’s something as sad as loss of language. Any time I tried to say a word or sentence here and there, it was met with patronizing amusement. Not exactly motivating me to keep trying. At the same time, I have fond memories of my 12-year old self attempting to speak Sarnami Hindustani with my Nani during my 6-week stay in Suriname. She didn’t laugh, she just listened. It was nice.

Fortunately, due to the rise of social media, our language has become more accessible to younger generations, with accounts like @sarnamibol: three Surinamese-Hindustani women who took matters into their own hands and chose to create more awareness for Millennials and Generation Z. One Insta post at a time, younger generations are carving out our own spaces, and we’re teaching each other.

I think that’s really revolutionary and beautiful.